Christopher Lane

Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities

Northwestern University

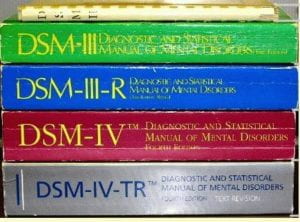

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) was first defined as a type of mental illness in 1980, when the American Psychiatric Association published an influential, massively expanded third edition to its diagnostic bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III for short).

Overbroad and Imprecise

At the time known as “Social Phobia,” a term many criticized as overbroad and imprecise (Cottle; Scott; Lane; Greenberg; Frances; Horwitz), the disorder joined more than a hundred newly created mental disorders, seven of them referencing anxiety alone.

Almost overnight, the new disorders vastly expanded a reference guide whose contents are daily invoked across the United States and much of the rest of the world, to authorize reimbursement for medical and clinical treatment. To much fanfare, the new disorders were widely touted as “evidence-based” and as “watertight,” amid a growing chorus of interest in “precision medicine” that could provide targeted treatment.

Loosened Criteria, More Diagnosis

The disorder was given its current name in 1987, when the APA brought out a revised 3rd edition with more than a dozen new disorders, on top of those it had first introduced in 1980, bringing the total to 112 new psychiatric conditions for which drugs could be prescribed.

In addition to giving the condition a more “user-friendly” name, the revised edition (DSM-IIIR) greatly expanded its criteria and removed one of its most-important brakes—that those with the condition needed to exhibit “a compelling desire to avoid” fear-inducing situations. After 1987, they had only to show “marked distress” for the diagnosis to be considered valid and reimbursable, for what quickly became mostly drug-related treatment (APA 1987:241).

By the time the APA brought out a 4th edition of its diagnostic manual 7 years later still, in 1994—an edition that would sell more than a million copies—recognition of the stark level of overlap between SAD and shyness led the APA to issue a warning—one that Allen Frances, Chair of the DSM-IV Task Force, later claimed few noticed or heeded—urging clinicians not to confuse the disorder with the personality trait. “Performance anxiety, stage fright, and shyness in social situations that involve unfamiliar people are common,” DSM-IV stressed, “and should not be diagnosed [as Social Anxiety Disorder] unless the anxiety or avoidance leads to clinically significant impairment or marked distress” (APA 1994:455).

“Embarrassment May Occur”

“The essential feature” of Social Anxiety Disorder, the text-revised edition of the DSM-IV announced, in one of its loosest definitions yet, “is a marked and persistent fear of social or performance situations in which embarrassment may occur… The individual fears that he or she will act in a way (or show anxiety symptoms) that will be humiliating or embarrassing” (APA 2000:450; my emphases). Examples include fear of eating and writing in public, concern about hand-trembling, avoidance of public restrooms, and “excessive fear of public speaking” (453).

However, because public-speaking anxiety is widespread and self-reported shyness, according to two Stanford psychologists, involves “nearly 50% (48.7% +/- 2%)” of North Americans (Henderson and Zimbardo), with percentages that replicate closely worldwide, critics have called the degree of overlap between SAD and shyness worrying and egregious (Cottle; Scott; Lane). They note that the DSM has over the years added routine fears that have the unavoidable effect of lowering the disorder’s diagnostic thresholds, making it too easy to be diagnosed, despite the APA’s 1994 warning about the outcome. In Saving Normal (2013), in a kind of mea culpa about now-“out-of-control psychiatric diagnosis,” though with less about his own role in loosening them, DSM-IV Chair Frances titled a relative section of the book “Social Phobia Makes Shyness an Illness” (152-53).

Given this multiyear emphasis on lowering diagnostic thresholds to make ever-larger numbers of people diagnosable, successive editions of the DSM have greatly increased—that is, artificially inflated—prevalence rates and, with them, the risk of misdiagnosis among those with mild-to-serious shyness, as with many other cognate conditions. Signs of “marked distress” in SAD, according to the manual, now include concern about saying the wrong thing—a fear afflicting almost everyone on the planet.

While the DSM indicates that for SAD to be diagnosed the subject must “recognize that the fear is excessive or unreasonable,” Henderson and Zimbardo note from robust data that shyness is similarly “defined experientially as discomfort and/or inhibition in interpersonal situations, in ways that interfere with pursuing one’s interpersonal or professional goals.” Accordingly, they put shyness on a spectrum that ranges “from mild social awkwardness to totally inhibiting social phobia,” arguing that it can, like SAD, “be chronic and dispositional.”

Much in Common, Tough to Disentangle

As such, shyness and SAD have much in common and may in nonextreme cases be difficult to distinguish. As University of Pittsburgh psychiatrist Samuel M. Turner and colleagues noted in Behaviour Research and Therapy, “The central elements of social phobia, that is discomfort and anxiety in social situations and the associated behavioral responses . . . are also present in persons who are shy” (Turner 1990:497; my emphasis). Hence the concern of DSM-IV that practitioners would confuse the two, in effect medicalizing a behavioral trait whose numbers can affect almost half of any human population.

According to Mary H. McCaulley and colleagues at Gaineville’s Center for Applications of Psychological Type, from an 8-year study of 75,000 cases, the percentage of shyness and introversion among 11th- and 12th-grade Americans was 37 for boys and 31 for girls. At older ages, the Center determined, similarly adopting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, the trait increased dramatically to affect 51 percent of boys and 43 percent of girls. Thereafter, including at graduate school, the numbers remained virtually unchanged, with 50 percent of men and 48 percent of women self-defining as shy or/and introverted (McCaulley, in Lane 2007:83).

Elastic Properties, Expanded Prevalence

Since shyness is widespread, situational, yet varies greatly in intensity and impairment, the prevalence rates for Social Anxiety Disorder have, unsurprisingly, proven highly elastic and depend heavily, as DSM-IV-TR puts it, “on the threshold used to determine distress or impairment and the number of types of social situations specifically surveyed” (APA 2000:453). “Epidemiological and community-based studies,” the manual continues, “have reported a lifetime prevalence of Social Phobia ranging from 3% to 13%… In one study, 20% reported excessive fear of public speaking and performance, but only about 2% appeared to experience enough impairment or distress to warrant a diagnosis of Social Phobia.”

Similar results were reported in 1994 when Murray Stein, a specialist in anxiety at the University of California at San Diego, and his team published an influential article about the disorder, “Setting Diagnostic Thresholds for Social Phobia: Considerations from a Community Survey of Social Anxiety.” The article drew from a single study—a random telephone survey of 526 urban Canadians—with results suggesting that social anxiety among them ranged from 1.9 percent to 18.7 percent, depending on the diagnostic threshold used (Stein 1994:412). That is, the problem affected either less than two in every hundred or almost one person in five.

Diagnostic Imprecision, Rampant Misdiagnoses

This brief history of SAD as a psychiatric disorder suggests that confusion about the condition’s prevalence and diagnostic threshold has plagued psychiatry and its patients since the edition’s vast expansion in 1980, while playing a substantial role in raising its medical profile. In 1993, just thirteen years after the disorder was formally approved, Psychology Today called it “the disorder of the decade” (“Disorder” 1993:22). By December 2000, the Harvard Review of Psychiatry was representing SAD as the third most-common mental disorder in the U.S, behind only depression and alcoholism (Rettew 2000:285). According to the 1994 National Comorbidity Survey, using DSM-IV criteria, as much as 12.1 percent of the U.S. population might have SAD and 28.8 percent—almost one in three—suffer from some kind of anxiety disorder (Kessler 2005:593).

Marketing SAD: “Is she just shy? Or is it …?”

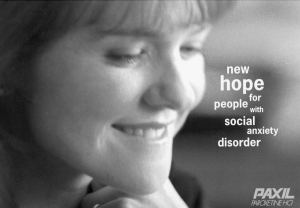

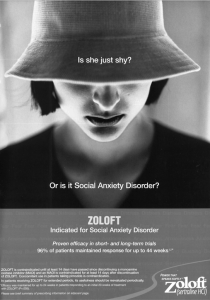

Throughout these years, with almost synchronized adjustment, marketing campaigns for pharmaceutical treatments of SAD took an already hazy distinction and blurred it even further, repeatedly muddying the line between the condition and shyness—that is, if you take the DSM seriously, between pathology and normalcy. One ad appearing in the American Journal of Psychiatry featured a young woman with downcast eyes and text that asked, “Is she just shy? Or is it Social Anxiety Disorder?” (reproduced in Lane 2007:138).

The product director for Paxil—the first antidepressant given an FDA license for SAD—volunteered to an interviewer: “Every marketer’s dream is to find an unidentified or unknown market and to develop it. That’s what we were able to do with social anxiety disorder.” The quotation appears in a 2001 Washington Post article entitled “Drug Ads Hyping Anxiety Make Some Uneasy” (Vedantam 2001).

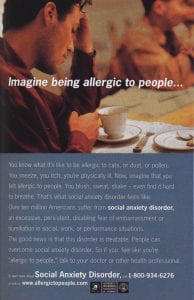

GlaxoSmithKline, Paxil’s manufacturer, went on to put more than $92 million behind a campaign aimed at convincing people that their shyness might in fact be a disorder treatable with drugs. The campaign was called “Imagine Being Allergic to People,” and it ran on bus shelters across the U.S. One poster featured a young man in an American diner staring forlornly into a coffee-cup (reproduced in Lane 2007:124).

“Freezing, Shrinking, or Failing to Speak in Social Situations”

Psychiatric literature on SAD has both noted and reproduced its broadly elastic properties. For instance, John R. Marshall’s Social Phobia: From Shyness to Stage Fright defines the disorder in its most expansive way (as his subtitle illustrates), emphasizing the role of common fears and concerns, including public speaking, and dealing with authority figures, social gatherings, and other forms of largely job-related embarrassment. Although Marshall acknowledges in his book, “There is no absolute score that indicates social phobia,” he includes diagnostic tests that invite readers to assess themselves, based on their fear and avoidance of “being criticized” and “being embarrassed and humiliated,” psychological states involving much-lower thresholds. “Patients in a treatment study for social phobia,” he adds, “had pretreatment scores … ranging from 19 to 56” (Marshall 1994:171-73).

The psychiatric literature on SAD is vast, tied to a host of drug trials and clinical studies aimed loosely at lessening suffering. Chronic anxiety can be a serious problem needing psychological and other kinds of treatment (for example, CBT, psychodynamic therapy, and, for situational anxiety, beta-blockers).

Nevertheless, a clear risk remains that by calling social anxiety a mental disorder and by drastically lowering its diagnostic thresholds to include such routine fears as public-speaking anxiety, the DSM has made an important distinction between ordinary shyness and SAD hazy and ambiguous. As Frances concedes, “Social Phobia Makes Shyness an Illness.”

With the most-recent (2022) text revised edition of DSM-5 stating that “in children, the fear or anxiety [indicating Social Anxiety Disorder] may be expressed by crying, tantrums, freezing, clinging, shrinking, or failing to speak in social situations,” leaving the criteria even-more routine and everyday, its audience still-more captive, in the sense that children can’t easily refute their diagnostic markers, the overlap between shyness and SAD is certain to stay controversial for years to come.

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING

Burstein, M, L. Ameli-Grillon, and K. Merikangas. 2011. “Shyness versus Social Phobia in US Youth.” Pediatrics 128.5:917-25.

Cottle, M. (Aug. 2, 1999) “Selling Shyness: How Doctors and Drug Companies Created the ‘Social Phobia’ Epidemic.” New Republic. 24-29.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition. (1980) American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd Edition Revised. (1987) American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. (1994) American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition Text Revised. (2000) American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition Text Revised. (2022) American Psychiatric Association, Washington, D.C.

“Disorder of the Decade.” (July-Aug. 1993) Psychology Today 26.4:22.

Frances, A. (2013) Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life. William Morrow, New York.

Greenberg, G. (2013) The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry. Blue Rider, New York.

Henderson, L, and P. Zimbardo (in press) “Shyness.” Encyclopedia of Mental Health. Academic Press, San Diego.

Horwitz, A.V. (2021) DSM: A History of Psychiatry’s Bible. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

Kessler, R. C., P. Berglund, O. Demler, R. Jin, and E. Walters. (2005) “Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication.” Archives of General Psychiatry 62.6:593-602.

Lane, C. (2007) Shyness: How Normal Behavior Became a Sickness. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Marshall, J. R., with S. Lipsett. (1994) Social Phobia: From Shyness to Stage Fright. Basic Books, New York.

Rettew, D. R. (2000) “Avoidant Personality Disorder, Generalized Social Phobia, and Shyness: Putting the Personality Back into Personality Disorders.” Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8.6:283-97.

Scott, S. (2006) “The Medicalisation of Shyness: From Social Misfits to Social Fitness.” Sociology of Health and Illness 28.2:133-53.

Stein, M. B., J. R. Walker, and D. R. Forde. (1994) “Setting Diagnostic Thresholds for Social Phobia: Considerations from a Community Survey of Social Anxiety.” American Journal of Psychiatry 151.3:408-12.

Turner, S. M., D. C. Beidel, and R. M. Townsley. (1990) “Social Phobia: Relationship to Shyness.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 28.6:497-505.

Vedantam, S. (July 16, 2001) “Drug Ads Hyping Anxiety Make Some Uneasy.” Washington Post.